VANCOUVER – The Novel Coronavirus, more commonly known as CoVID-19 has now been with us for more than 9 months with no sign of abating. Our best chance at normality is for the widespread vaccination of the global population. While significant progress has been made on multiple vaccines, production and distribution hurdles mean that widespread vaccination is unlikely to be achieved until the latter part of 2021. From a public health standpoint, there have been more than 42 million cases globally, with active cases standing at more than 10 million as of writing. Canada is currently battling approximately 2,600 new cases per day; however, the distribution of these vary significantly by geographic region.

From an economic perspective, the effects of the lockdown have been more widely felt among Canadians. According to the Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey, between February and April 2020, which was considered the peak of the lockdown, unemployment rose from 5.6 percent to 13 percent. It has since returned to 9 percent as of October. With official unemployment rates still above the peak of the 2008 global financial crisis, it is difficult to say with any certainty if an economic recovery is underway. Although unemployment rates provide some insights into the impact of CoVID-19 on the economy, they tend to mask a significant amount of the damage, downplaying the vulnerability of the economy.

"What happens when one has a job, but is absent from work? Or when someone is unable to actively look for work?"

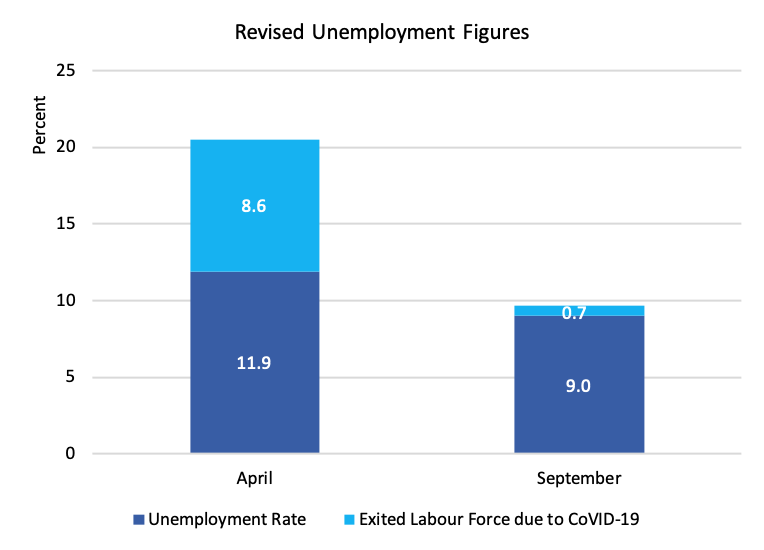

Based on the Statistics Canada definition, employment refers to any person who ‘during the reference week did any work for pay or profit, or had a job and [was] absent from work’. Juxtaposed, unemployment refers to any person who ‘during the reference week, [was] available for work and [was] either on temporary layoff, had looked for work in the past four weeks or had a job to start within the next four weeks’. But what happens when one has a job, but is absent from work? Or when someone is unable to actively look for work? The answer is that they are considered to be ‘neither currently supplying nor offering their labour services’ and fall outside of the labour force. The result is that they are a hidden figure and are no longer included in the statistics. While this is widely known among Labour Economists, its importance has become amplified as a result of the nature of the CoVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown. With schools and daycares shut down, many parents have been left to tend to domestic responsibilities such as caring for children, the sick and the elderly. Moreover, with businesses closed to comply with lockdown measures to limit the spread of the virus, there are few jobs for one to actually apply for. While the Labour Force Survey recorded the peak of unemployment at 13 percent, revised calculations put it closer to 20.5 percent when those who have exited the labour force are factored in.

"While the Labour Force Survey recorded the peak of unemployment at 13 percent, revised calculations put it closer to 20.5 percent when those who have exited the labour force are factored in."

To account for this hidden figure in unemployment (ie. those who are neither employed or unemployed and have instead exited the labour force), one has to determine the number of individuals that have fallen out of the labour force. A simple way to do this, is to utilize the labour force participation rate from before the lockdown went into effect, instead of the adjusted rate after which many have already fallen out of the labour market. In February 2020, the labour force participation rate, before lockdown measures came into effect was 65.5 percent; as opposed to the adjusted labour force participation rate of 59.8 percent at the peak of the lockdown in April 2020. This is then multiplied against the actual working age population for April (ie. those above 15 years of age), arriving at a labour force of 20.36 million. This is then subtracted from the April labour force calculations of 18.6 million, suggesting that 1.76 million fell out of the labour force due to CoVID-19 related reasons that would have otherwise been there. When added to the unemployment figure of 2.42 million, total unemployment increases to 4.18 million or 20.5 percent at its peak.

Although things have begun to rebound, with revised unemployment figures dropping from 20.5 percent in April to 9.7 percent in September, the majority of those entering the labour force can be seen in a return to part time employment (+38.3%) as opposed to full time employment (+9.7). According to a recent survey by Statistic Canada, more than 1 in 5 part time workers (22.7%) have indicated that they wanted full time work but were unable to find it. This suggests that a sizable portion of the employment gain has been involuntary.

Taking a more nuanced look at the demographic composition of the population shows that employment losses between February and April disproportionately fell upon women (-16.9%) as opposed to men (-14.6%), among youth aged 15-24 (-34.1%) compared to older age groups (25 years and over) (-12.8%) and among very recent immigrants who have been in the country for less than 5 years (-23.2%) than it was for the Canadian born population (-14%). While part of this can be explained by the fact that these groups are disproportionately represented in industries that suffered from the greatest declines (ie. Accommodation and Food Services), it also reveals certain vulnerabilities in Canada’s labour markets. There is clearly much to be done when it comes to getting the economy back on track, but it is important for policy makers to keep in mind that the devil is in the details. By addressing such frailties, Canada has an opportunity to build a more robust and resilient economy.

Kyle Farrell is Managing Partner and Chief Urban Economist at Economic Pulse Analytics. He works closely with local governments to provide them with population, housing and employment forecasts to make more informed decisions about their future. He holds a PhD with specialized knowledge in Urban Economics and regularly consults for the United Nations.

Comments